Learning some of the peninsula’s tumultuous history will help visitors discover a treasure trove of semi-forgotten, overlooked sites.

By Chris Drum Berkaya

How far back does Bodrum Peninsula history go? More than 5,000 years! In 1991 archaeologists investigated Peynir Çiçeĝi Cave in Gündoğan and found painted pottery and jars, and a stone axe dating from the Chalcolithic era (5,000- 3,000 BC). It is a rare example of a Chalcolithic cave settlement in Western Anatolia. The Bronze Age (3,000-1,200 BC) was an active period in Anatolia when copper and tin alloy tools and bronze weapons were made. Late Bronze Age Mycenaean tombs have been found on the peninsula, dated between 1,400 -1,200 BC.

Around 1,000 BC the Dorians came through Greece and the Aegean islands in the migrations after the Trojan Wars. They founded a settlement, using the name Halikarnassos, on the small island in the bay. They lived beside the indigenous people, the Carians and Lelegians, who lived inland and kept distinct identities until around 400 BC. The Lelegians lived on the hilltops in eight settlements built in distinctive dry stone walls. Pedasa fort was originally Lelegian and the excavated site is worth visiting in the hills above Konacık. The other hilltop settlements were Syangela and Theangela above Alazeytin and Çiftlik villages, and Telmissos above Gürece and Termera above Bağla. The stones and walls still lie at those sites and some ancient paths can be walked or are recreated by the Lelegian Way.

The Carians gave their name to the region of Caria; from the Meander Valley at the present Lake Bafa, to ancient Caunos at Dalyan. They were known as mercenaries; Homer recounts that they fought as allies with Troy. Halikarnassos was allied with Ionian cities between 700 and 500 BC when the Carian cities were under control of the northern Lydian kingdom based at Sardis until King Croesus died.

Beside the Bodrum Castle walls are three statues of famous ancient figures of Halikarnassos; ‘King’ Maussollos, his wife-sister Artemisia II, and Herodotus, often called the Father of History, a writer and traveler (484-425 BC) who gave us the earlier history of the region.

At the end of the struggles between the Lydians, and the ‘superpowers’ of Athens and Persians, the Carian area came under Persian rule, under their appointees of local satraps. The first satrap, Hyssaldomos of Mylasa (now Milas), was succeeded by his son Hecatomnos in 392 BC. When his son Maussollos came to power in 377 BC he moved to Halikarnassos and started a huge rebuilding program in Hellenistic style.

It was also a resettlement, forcing the peninsula’s population to live in the city except those at Myndos (today’s Gümüşlük) and eastern Syangela. He built a palace; one last wall has been identified in the grounds of Bodrum Castle. Today fragments of Maussollos’ city walls can be seen on the Göktepe hill around the theater. The most impressive section is restored at Myndos Gate, one of the two gates to the city.

Another outstanding monument is the Ancient Theater, which seated 10,000 people. Though it was altered later in Roman times, it is one of the oldest theaters in Anatolia. It can still hold 3,500 for modern-day concerts.

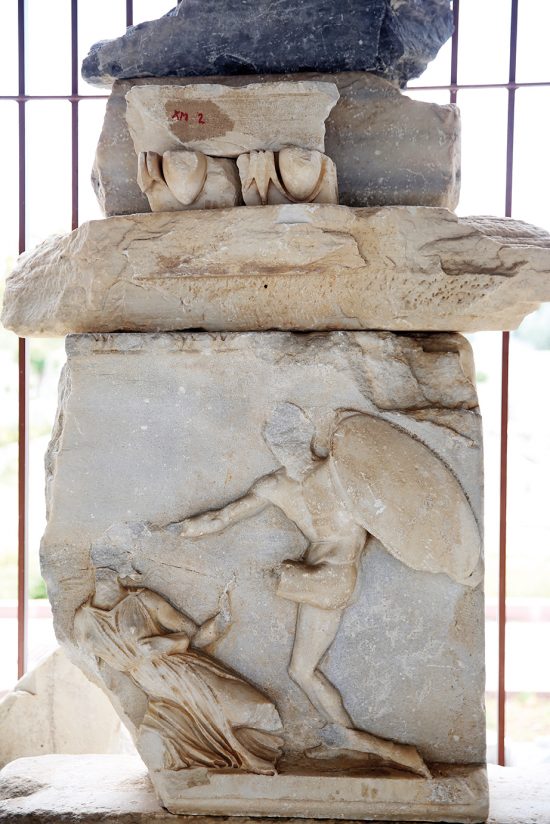

Maussollos started to build himself a monumental temple tomb with the best sculptors of the known world. However, he died after 24 years in power, and his sister-wife Artemisia II completed the massive five-story high building known as the Maussolleion of Halikarnassos and three years later she was buried with him. It became known as one of the Seven Wonders (of the Ancient World) and gave the world the word ‘mausoleum’. The small Museum and excavations give a glimpse of its glory. This was the peak of the great Halikarnassos city.

After Artemisia the succession passed to the brothers, but the mighty Macedonian army under Alexander the Great arrived at the gates in 344BC. The city fought back under siege, coming close to giving Alexander his only defeat. Eventually, a desperate battle at the Myndos Gate was lost and the city sacked, leaving only the Maussolleion unscathed. Alexander gave the city, and Caria, to Ada, the youngest sister of Maussollos, who had been banished earlier by her brother. It is believed that it was her tomb containing a skeleton and gold crown that was found in 1989 in a building site. An entire exhibition room was given to display restored ornaments, the sarcophagus and a life-sized replica of Ada in the Bodrum Museum.

The city never recovered its glory after Alexander’s plunder, losing its independence when it was subsumed into the Roman province of Asia, and suffering in the Roman battles. Brutus and Cassius’s navy passed through Myndos-Gümüşlük port on the way to fight Mark Antony and Cleopatra near Rhodes in 46 BC. Myndos later became a Roman-Byzantine port and city. Not much remains apart from the underwater harbor wall and stone pylon, and marble columns left built into walls.

After 100 AD Halikarnassos Peninsula enjoyed a peaceful existence under the Roman Empire, and once Christianity was adopted, it was ruled by the Bishopric at Aphrodisias. The fourth to sixth centuries saw the Byzantine town and port of Strobilos founded at the foot of Aspat mountain. It is thought there was a great deal of pilgrim traffic between Kos and Iassos and the hermit monasteries of Herakliea. At least one chapel has been excavated from that era.

After the Arab raids of the seventh century, the Byzantines remained in control until the eleventh century, then settlement by Turkish tribes and the Menteşe Beyliks’ capture of the Halikarnassos saw a small Turkish fort built near the Bodrum Castle. The Maussolleion had for 1,500 years, but a rare catastrophic earthquake in the thirteenth century brought it down. The knights found only rubble and used it for building the castle. Look closely and see odd marble pieces, and the distinctive green andesite blocks originally mined for the Maussolleion at Koyunbaba quarry, which can still be visited today.

The Ottoman Turks built settlements, the mosques and the town Han, now a nightclub. The main Ottoman-era monuments are the low stone wall and the Ottoman Tower, now an art gallery, set into the wall of the Milta Marina. This guarded the shipyards tasked with building the sultan’s ships to replace those lost in the catastrophic naval battle of 1770 against the Russians at Çeşme. Several Ottoman tombs lie in the small cemetery in the gardens of the marina. Around the same time the old mosque on Harbor Square (1723) and the beautiful little Tepecik mosque (1737) were built. A notable private house, once known as the Pasha’s house, on Bodrum Harbor was restored by Atlantic Records founder, Ahmet Ertegun, where his celebrity guests stayed in the 1970s–90s and contributed to the growth of tourism.

During the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, Greek Christians built the chapels around the peninsula. The best examples are the Eklisia in Gümüşlük, at Kadıkalesi Chapel, and Gara Chapel in a Bitez orchard.

Bodrum Castle is the city’s tangible connection between the past and recent times. It was used as an Ottoman fort and prison until 1915. It suffered severe damage from bombing by a French warship during World War I. The lives of farmers and seamen carried on during the early Turkish Republic, days when the ridgetop stone windmills were built, and some larger houses were erected in mandarin and olive orchards before tourism arrived. Bodrum Castle was renovated and reopened as the Bodrum Museum in 1964.

The seafaring history of the city is told in the Bodrum Maritime Museum, which also displays personal effects of the ‘Fisherman of Halikarnassos’, Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, a Turkish writer who became strongly associated with Bodrum. His books and articles helped spread awareness of the city’s history, and paved the way for it to become a major tourist attraction.

“Don’t you dare to hope that you will leave as you came, like many others before you have done. They all have left while their minds stayed in Bodrum,” wrote Kabaağaçlı. It is enshrined, almost as a warning, at the entrance to Bodrum.